Everything We Think About Teaching is Wrong

How to design courses that students actually learn from.

The Second Draft: #0047

Why I Wrote This

As I’ve been working on this series, I knew—but never truly appreciated—how wrong our approaches to education are.

We load students with concepts, frameworks, and theories, then expect them to “apply” it all as they “create” some bigger artifact (or smaller artifacts along the way).

And that actually, doesn’t work.

What You’ll Get

→ Why five-year-olds outperform MBAs on a design challenge (and what that says about Bloom’s Taxonomy)

→ The five biggest myths we still believe about learning and expertise

→ How more knowledge doesn’t actually form the foundation of transferable skill

→ Why apply, synthesize, and create aren’t steps at the top of learning, but the engine that drives it

→ And how the Big Hairy Audacious Problem (BHAP) creates the structure for the right kind of learning to happen every time

The New Shape of a Course

We started this series looking at how teaching changes when you accept that students can outsource any work product to AI.

We introduced:

→ AI Actualism—the reality that AI just is,

→ the distinction between Protected and Prompted Knowledge—what you need to know in order to get the outputs you want,

→ and the idea of Fractal Teaching that treats every lesson as a nested system of anchors and applications.

Next, we followed up by showing why assessment is dead,

and how Assessment through Learning could replace assessment of/for learning.

We zoomed in on Quadrant 4: the Expertise Zone,

where students have enough protected knowledge to get the results they need through their prompting.

Now we drill down even more on the practical side,

to start exploring what it looks like to bring this to life in the classroom through what I’m enjoying calling a Big Hairy Audacious Problem (BHAP).

The Marshmallow Tower

Have you done this thing?

18 minutes

20 sticks of spaghetti

one yard of tape

one yard of string

and a marshmallow . . .

which must be placed on top.

Even if you’ve never done it,

you’ve probably heard how this plays out.

Apparently, the consistent finding in hundreds of trials is that five-year-olds are significantly more successful than recent business school graduates

5-year-old average: 26 inches

Business grad average: 10 inches

🤯

I find those stats incredibly hard to believe also,

but Gemini and Perplexity corroborated and who am I to argue?

Here’s why this happens.

Kindergarteners: Learning by Doing

→ They immediately start building and testing structures.

→ They treat every attempt as a cheap experiment, quickly building, failing, and learning.

→ They test the marshmallow’s weight early and often, identifying the “hidden assumption” (that the marshmallow is light) right away. This allows them to adjust their design.

→ They collaborate naturally without competing for status.

MBA Students: Planning then Doing

→ They spend a large amount of their limited time planning, strategizing, and debating roles.

→ They commit to a single, elegant solution and spend most of their time executing that one plan.

→ The crucial moment comes at the very end when they place the marshmallow on top (the hidden assumption).

→ The marshmallow, which is heavier and denser than they assume, causes their carefully constructed structure to collapse, leaving them no time to make fixes.

Why didn’t I include those stats in my series on the higher ed scam!?

Bottom Up

Obviously, most of education is built on the MBA approach.

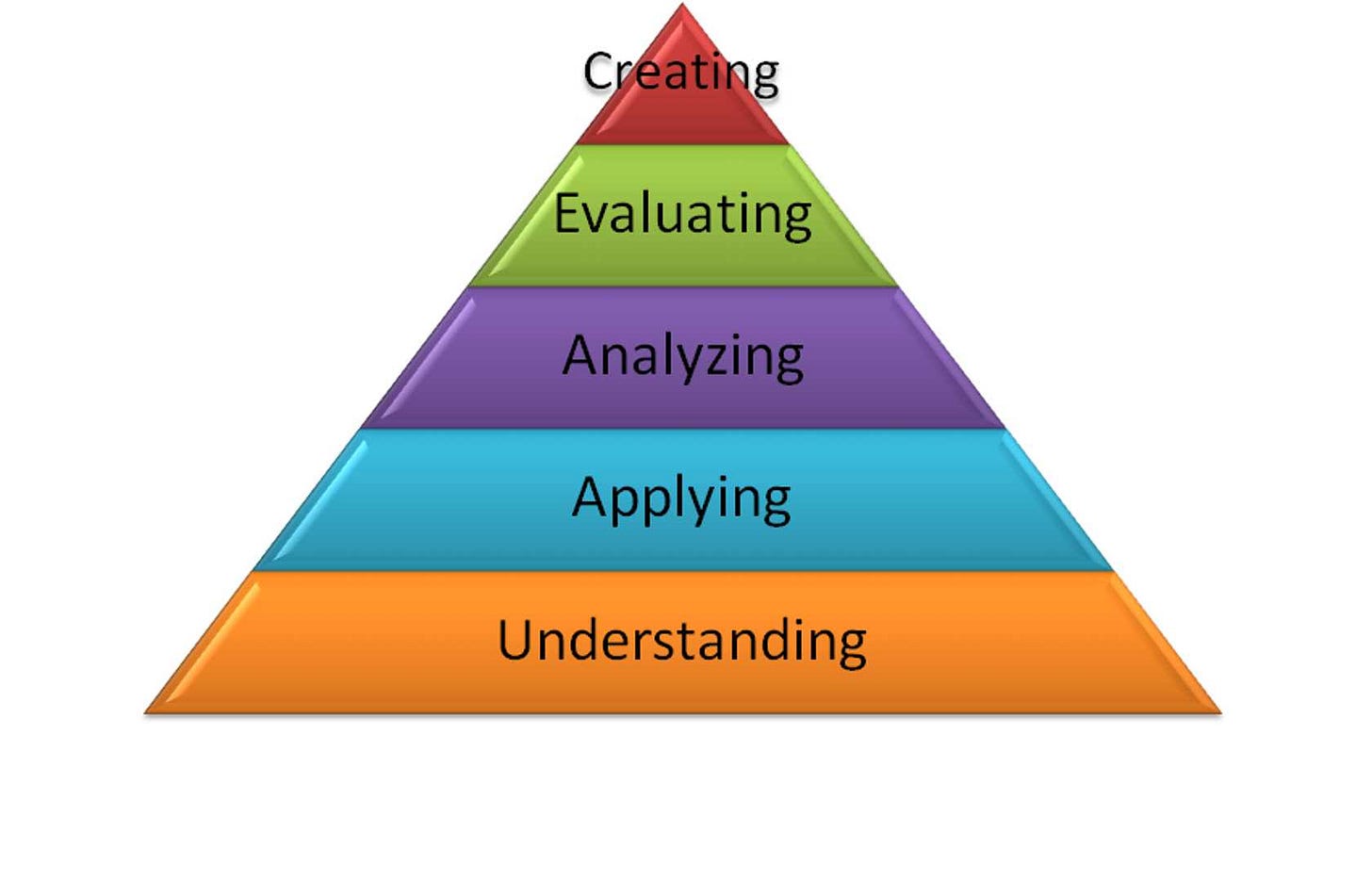

Think of Blooms Taxonomy as the way this works,

moving from the bottom to the top of the pyramid.

We spend most of our courses building the foundation:

definitions, key terms, concepts, theories, and frameworks.

Then, the course culminates in a project that gets at the height of the pyramid,

those “higher-order” skills of synthesis, evaluation, and creation.

But—and here’s the irony—this is exactly what the MBA students did!

They followed Bloom’s Taxonomy perfectly.

They mastered the concepts, developed the frameworks, understood the principles—and then, with two minutes left, tried to create the tower with all that knowledge by placing the marshmallow on top.

And what happens?

The spaghetti tower (and Bloom’s pyramid, ironically the same shape😉) collapses.

And why does this happen?

Because we believe and have taught that application/creation is just “concepts + execution.” That if you know enough content, your ability to do something useful with it naturally follows.

But that’s not how anything actually works!

The kindergarteners don’t know any concepts. They can’t define or wouldn’t even think to consider “structural integrity” or “load distribution.”

But as they work the problem,

they’re continually developing the actual heuristics of application:

→ build stuff

→ see what happens

→ triangles are strong

→ heavy things make things fall over

→ what happens when we add this there . . .

They’re not applying concepts

—they’re building practical expertise through iterative engagement.

Education’s Biggest Mythconceptions

There are many more, but here’s a few things we get catastrophically wrong about how learning actually works (and why we can’t seem to figure out how to teach in an AI world).

Myth 1: Understanding is the foundation of application

We talked about this one already.

We structure entire courses on this assumption:

first understand the concepts, then you’ll be able to apply and create with them.

That’s exactly what the MBA students did.

And their tower collapsed.

Because understanding and application aren’t sequential

—they’re intertwined.

The kindergarteners don’t understand why triangles are strong, but they can build with them.

Through building, they develop intuitions that eventually become understanding.

Application isn’t what you do after understanding.

Often, it’s how understanding develops.

Myth 2: Cognitive skills are transferable

Even within a domain, transfer is shockingly limited.

A student who can analyze Shakespeare doesn’t automatically transfer that skill to analyzing contemporary poetry. Someone who solves calculus problems brilliantly might struggle with calculus-based physics.

Why?

Because thinking is a skill comprised of highly specific patterns of recognition and response, tied to particular contexts and cues.

You might want to memorize that one and share it!

But we’re taught in popular educational thought that all students need is to learn how to “think critically.” And if they can think critically about one thing, they can think critically about anything.

That’s not how cognition works.

Every new context requires rebuilding patterns of recognition and response,

even within the same field.

Myth 3: Practice makes perfect

Wrong—deliberate practice makes perfect.

And deliberate practice takes:

The help of a teacher

In a protected environment

With opportunities for reflection

Ongoing and meaningful repetition

Structured problem-solving practice

Exploration of alternative approaches

Informative feedback based on performance

Now consider how we actually teach:

content dump → single application → grade → move on.

We give students one shot at the marshmallow tower

and wonder why they never develop structural intuition.

Myth 4: Knowledge is information storage

Even within liberal arts institutions and interdisciplinary programs,

we tend to teach as if the brain is a file cabinet

—learn this fact, store it, retrieve it.

But cognition works like a spider web, not a filing system.

We make sense of the world through schema.

Every new piece of information only makes sense through its connections with other things we know. Understanding is less about storage and more about relationships.

The richer the web of connections, the deeper the understanding.

This is another reason why kindergarteners beat MBAs. They weren’t drawing from disparate ideas, they were building a web of relationships in-real-time: weight affects stability, triangles distribute force, testing reveals problems. They didn’t actually say or think exactly that, but that’s what functionally happened.

Myth 5: More knowledge equals better decisions

Here’s a big one:

we think experts know more than novices.

They don’t.

They often know less.

Or at least they think about less!

Experts have pruned away the irrelevant.

They’ve developed mental models and heuristics that wall off what doesn’t matter so they can focus on what does.

But we do the opposite.

We teach as much content as possible under the false assumption that without it,

students will never function as experts!

In a very real sense, the MBA students knew too much and ended up asking too many questions.

How should we plan?

Who should have what role?

What lesson is this teaching?

How can we make the most of our resources?

The kindergarteners knew enough only to ask one thing:

Will this stand when I put the marshmallow on top?

The BHAP Alternative

Here’s the big idea, let’s not move past this too quickly 👇

Kindergarteners, with literally no formal schooling,

outperformed working professionals with 18 or more years of formal schooling.

We have to let this sink in.

We have to sit here and realize the power of these experiments and what they mean for our approach to education.

Folks. We are doing something tragically and terribly wrong in education.

Okay, one more time, for effect:

Kindergarteners, with literally no formal schooling,

outperformed working professionals with 18 or more years of formal schooling.

And for one main reason:

they were intuitively developing heuristics through iterative practice.

The kindergarteners weren’t trying to apply abstract principles.

They were just building practical knowledge through direct engagement with a problem.

This is where the Big Hairy Audacious Problem comes in.

Instead of building toward application, you start there.

The marshmallow goes on top from minute one.

Every concept, every piece of content, every skill gets learned through the lens of application.

Not applied after learning—developed through iterative engagement with real problems.

Let’s Make it Real

There are perhaps two thoughts going on right now:

1/ How do I bring this to life? Show me what you mean!!!!

2/ Isn’t this just problem, project, or process-based learning?

First, thank you! That’s our plan!

Next time, we’ll continue putting some flesh on this skeleton as we build an entire system aimed at answering one question:

What does it take to teach in the era of AI

Second, there are of course similarities. I can’t just invent entirely new categories of how humans interact with the world! However, I do want to assure you that the approach itself and the layers we add to it are beyond mere problem, project, and process-based approaches.

Next issue we’ll look at what a BHAP actually takes to design, launch, and sustain across an entire course.

To my loyal patrons! Those of you who invest in this space with your hard-earned, real dollars . . .

I’m giving you a deeper dive into why BHAP works where every other progressive pedagogy fails.

Below you’ll find:

✔️ why Big Hairy Audacious Problem (BHAP) isn’t just another spin on project, problem, or process-based learning

✔️ how AI changes what problems are even attemptable

✔️ why the real measure of learning isn’t the quality of the solution, but the evolution of capability that emerges through every failure, rebuild, and refinement.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Second Draft to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.